Abstract

Background: AL amyloidosis (AL) remains an incurable and devastating disease that is often misdiagnosed or diagnosed late. Keys to better long-term outcomes include early diagnosis, multispecialty collaboration, and effective interventions; however, it is unclear how prepared clinicians are to manage AL. A study was undertaken to assess hematologists/oncologists (hem/onc) ability to diagnose, monitor, refer, and manage patients with AL.

Methods: An incentivized survey was developed utilizing current evidence-base and best practices in AL. The assessment included both multiple choice and free form text questions that clinicians completed confidentially on-line starting on May 10, 2017. The survey continues to recruit participants. Thirteen questions were asked regarding diagnosis, education interests, referral approaches, monitoring, and treatment of patients with AL.

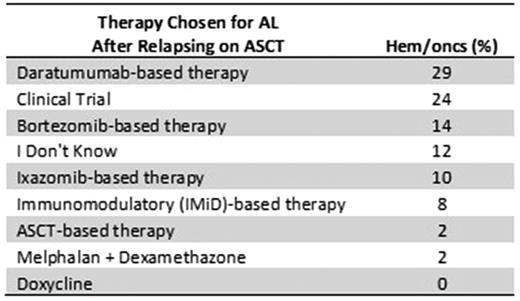

Results: As of July 2017, 51 hem/oncs participated in the assessment: 47% were from private/group practice, 27% local/community, and 25% from the academic setting. 88% of respondents work with other specialists to manage AL, which included nephrologists, cardiologists and neurologists (84%, 80%, and 42%, respectively). The number of patients with AL seen by study participants each year was: 0 (10%), 1-3 (31%), 4-7 (37%), 8-12 (18%), and > 12 (4%). After diagnosing AL, the majority (76%) of respondents would manage the patient at their clinic. Selection of therapy varied on patient presentation. At diagnosis, the majority selected bortezomib-based therapy in patients with cardiac or renal involvement (33% and 49%, respectively); however, in patients with neuropathy, hem/oncs chose a variety of therapies. In patients with AL after relapse on bortezomib therapy, the majority selected autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) (27%). In a patient that relapsed after ASCT, the majority selected daratumumab-based therapy or clinical trial (29% or 24%, respectively) (Table 1). Respondents' primary goals of therapy included: improvement in overall survival (78%), improving quality of life (67%), organ response (65%), hematologic response (24%), and minimizing therapy side effects (18%). When asked about which biomarkers they follow, respondents chose free light chains (86%), proteinuria (67%), B-Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) (47%), N-terminal pro-brain BNP (NT-proBNP) (45%), and troponins (37%). Clinicians also expressed interest in education on a variety of emerging therapies including NE0D001 (55%), daratumumab (51%), GSK2398852, CAEL101 (41%), and izaxomib (41%). The top education needs cited were awareness/understanding of current treatment options (47%), emerging therapies (45%), diagnosis (37%), clinical trials (35%), and assessing organ response (31%). Finally, the respondents indicated that the top three unmet needs in diagnosing and caring for patients with AL included education on treatment options, differential diagnosis, and managing therapy side effects.

Conclusions: AL is a complex disorder that requires a high clinical acumen to diagnose and manage. This research identified that apart from consensus to use a bortezomib-based regimen, there is significant heterogeneity in selection of therapies. Biomarker use for monitoring is inconsistent, especially for NT-proBNP. Although referral to specialists are critical to care, such referrals are variable. The lack of approved therapies for AL and an absence of consensus treatment guidelines may be contributing to the disparate treatment approaches. Education to increase awareness of clinical gaps of hem/oncs as well as development of consensus guidelines that address referral, biomarkers and therapeutic options are needed.

Table 1. Treatment Selection in AL after ASCT Relapse

Gertz: Celgene, Novartis, Smith-Kline, Prothena, Ionis, Amgen: Honoraria; Millennium: Consultancy, Honoraria.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.